Legal Mailbag – 6-12-18

By Attorney Thomas B. Mooney, Neag School of Education, University of Connecticut

The “Legal Mailbag Question of the Week” is a regular feature of the CAS Weekly NewsBlast. We invite readers to submit short, law-related questions of practical concern to school administrators. Each week, we will select a question and publish an answer. While these answers cannot be considered formal legal advice, they may be of help to you and your colleagues. We may edit your questions, and we will not identify the authors.

Please submit your questions to: legalmailbag casciac

casciac org.

org.

Dear Legal Mailbag:

Dear Legal Mailbag:

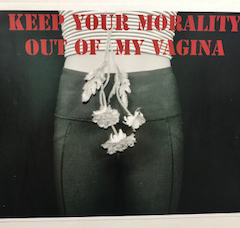

Spring is the season for art shows, band concerts and short shorts. At our annual spring art show this year, one of my teachers displayed a poster with an image that some parents and others thought was over the top and inappropriate. A picture of the image is included for your review. Some parents took to social media and expressed their concerns in intemperate terms, others called me to question my competence, and some even went to the superintendent to complain. It’s still unclear if the artwork was actually student-created, but either way I have to deal with it.

I know that the United States Supreme Court has provided some guidelines for addressing student speech in its decisions in Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier (1988) and Bethel School District No. 403 v. Fraser (1986). However, I don’t know what the standard is for taking down artwork. Help!

Thank you,

Speechless Over Art

Dear Speechless:

Take heart that the school year will soon be over. For now, Legal Mailbag is here to help, though your prior knowledge of the Hazelwood and Fraser cases makes me wonder if you really need help. In any event, let us briefly review those decisions for the general reader so that we can all understand why you have every right to take down the offending image.

Any discussion of student free speech rights perforce starts with Tinker v. Des Moines Independent School District (1969), where the United States Supreme Court ruled that students do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.” Under Tinker, school officials may regulate individual student speech in school only if they reasonably forecast material disruption or substantial interference with the educational process or invasion of the rights of others.

By contrast, in 1986, the Court ruled that school officials do not have to tolerate vulgar speech by students in school, irrespective of whether such vulgarity causes a disruption. In the Fraser case, a student was suspended for three days after making a vulgar speech at a school assembly (Google it if you want). The lower courts relied on Tinker and ruled, absent disruption, the suspension violated Matthew Fraser’s free speech rights. However, in Fraser, the United States Supreme Court created the first exception to the Tinker rule to hold that vulgarity in school need not be tolerated because school is a place for students to learn about decorum.

Two years later, the Court created the second exception to the Tinker rule in a case involving a challenge by student editors of the school newspaper over what they claimed was censorship in violation of the First Amendment. Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier (1988). There, the principal spiked stories on teen pregnancy and children of divorce, and the lower courts held that the school administrators had violated the free speech rights of the student editors. However, the Court again reversed, holding that school administrators may regulate student speech in school-sponsored activities (such as the school newspaper) as long as they have a “legitimate pedagogical interest” in doing so. Given the potential for embarrassment of students and for violating their privacy interests if the stories had been published, the Court ruled that, in killing the stories, the school administrators had acted within their authority and without violating the First Amendment rights of the students.

The Hazelwood rule has since become the guide in considering student free speech rights in school-sponsored events, such as the school play, the school newspaper and even books in the curriculum or library. Given that the art show was school-sponsored, the Hazelwood rule applies to your situation. You have the right to regulate the display of art if you base your decisions on legitimate pedagogical concerns. Here, you had more than ample pedagogical concern that such a poster not divert attention from the purpose of the art show – to celebrate student work. Moreover, while the student who posted the work might have been eighteen years of age, the show was for all ages, and the courts have been tolerant of school officials’ efforts to keep sexual matters out of school events.

Finally, I note that you expressed uncertainty over whether the poster was even created by a student. If indeed a teacher or other school employee created the poster, you have even more discretion. The Court has ruled that when teachers and other employees are performing their job duties, they do not have the right to assert free speech claims regarding the regulation of their conduct and any related disciplinary action.